NOTE:

This article is dynamic in that it will change over time as new or

different information is found.

First published 21NOV06 - current revision 25NOV2006

The idea of telling stories first with paintings on cave walls, then hands then puppets casting shadows on a wall or screen goes back to pre-history. Such entertainment were the seeds from which sprang motion pictures.

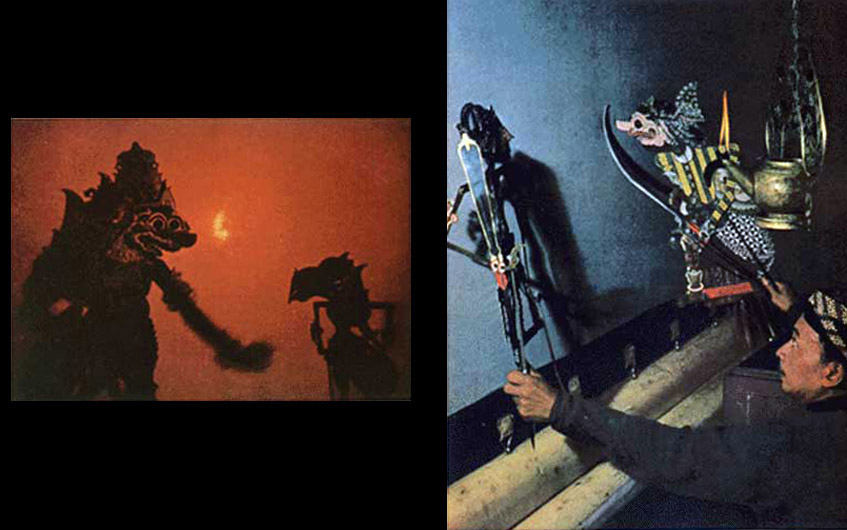

One form is still seen today in parts of Indonesia, and is called Wayang Kulit, dating back to at least the first 100 years AD.

The concept is simple: hang a sheet in a darkened room. Have the audience on one side. On the back side, a candle or lantern casts light upon the back of the screen. The puppet master (dalang) holds the puppets up in the light, casting distinct, black silhouettes with excellent detail.

Elaborate stories, sometimes hours long, would hold entire villages entranced in the days before films and TV.

Shadow plays evolved and eventually moved into Europe in the 16-1700’s.

The simple shadows were eventually replaced by the projection of images, evidencing the trend toward motion pictures.

We jump to ca. 1920, when the energetic 25 year-old inventor Laurens Hammond (1895-1973) conceived of an idea for a stereoscopic motion picture system.

His first demonstrations used still projectors. This impressed enough for Hammond to obtain hundreds of thousands of dollars of investment to develop the idea.

The main focus of the system was the production and exhibition of moving pictures, but at some point, Hammond came up with a variation: the stereoscopic shadowgraph.

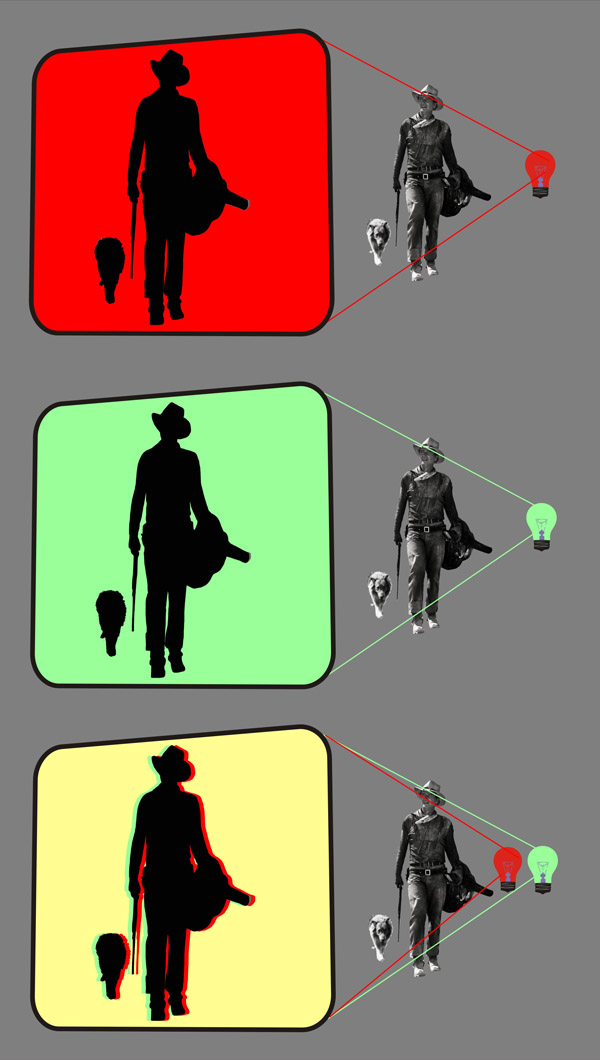

The principle was simple, but difficult to easily explain.

In a theater, exchange the normal projection screen with one more translucent.

On the stage behind the screen, place two, high-intensity light sources. Arc lights or, today, quartz, which produce highly specular (collimated) light. This is needed to produce sharp shadows on the screen, which would be perhaps 30’ away. The lights are placed side-by-side perhaps 2-3” apart.

Put a red filter in front of one light and a green filter in front of the other.

Cover the green light. The screen is red from the red filtered light.

Let’s place an object on the stage, say half way between the lights and the screen.

Now we see a black silhouette of the object on a “red screen.”

Cover the red light, uncover the green light.

We now have a black silhouette of the object on a “green screen.”

What you might not notice is that each silhouette is slightly to one side of the other. This is because the two light sources are slightly to one side of the other. This produces shadows with parallax.

Uncover both lights and we see the central most of the object as a black silhouette, with a green edge ("fringe") on one side, and a red fringe on the other.

This is an anaglyph. When viewed with green/red 3D glasses, the silhouette will appear to either be stereoscopically off the screen, seeming to be in the theater space, or behind the screen, more like “through” the screen.

If the object seems to be off the screen, we move the object back, away from the screen toward the lights. The object’s silhouette will get larger and will come further off the screen!

You can have objects off or in the screen, but not both at the same moment. To change from ‘off’ to ‘in’ the colored filters are swapped between the lights. This isn’t good to do from the audience perspective, and I don’t think was done back then.

If the filters on the lights and in the glasses are proper, the effect can be excellent.

For his Teleview program, Hammond simply replaced the colored filters with alternating shutters. The shutters were synchronized to the viewing glasses: left light for left eye with right light and right eye blocked.

This would have looked great, as it wasn’t anaglyph. And from the written record, it was great. A wonderful stereoscopic presentation.

The shadowgraph was made part of the Teleview program, which opened on 27DEC1922 at the Selwyn Theatre, NYC.

According to the patents themselves, there were four patent applications covering the Teleview system: overall concept, seat mounting, viewing device, shadowgraph. I have not found a patent for the viewing device which seems odd. It was a wonderful design. But it appears it wasn’t granted.

The Teleview only played 24 days, closing 20JAN23.

Hammond filed his patent for stereoscopic shadowgraphs on 23JAN23, just three days later.

His patent was a simple stereoscopic shadowgraph concept using colored lights for anaglyph 3D (as described above). VERY oddly, he didn’t also include his Teleview (sequential) viewing system.

I do not know exactly when, but sometime in 1923, Hammond got to demonstrate a “stage effect” to Florenz Ziegfeld (1869-1932). The Ziegfeld Follies (1907-1931) was an extremely successful “fixture” in NYC, featuring the best in song, dance, comedy—done up with excellent production.

Florenz Ziegfeld.

According to Hammond, Ziegfeld didn’t understand the concept well, though incorporated it in his revue anyway.

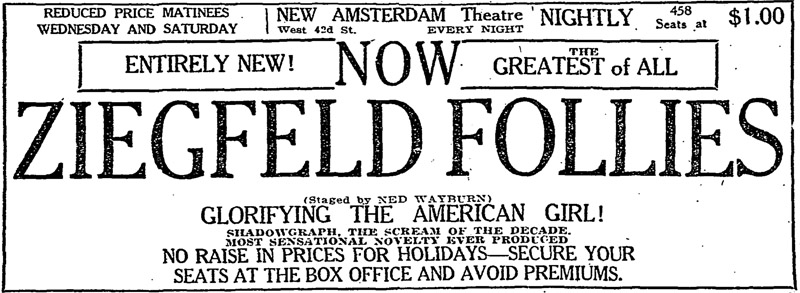

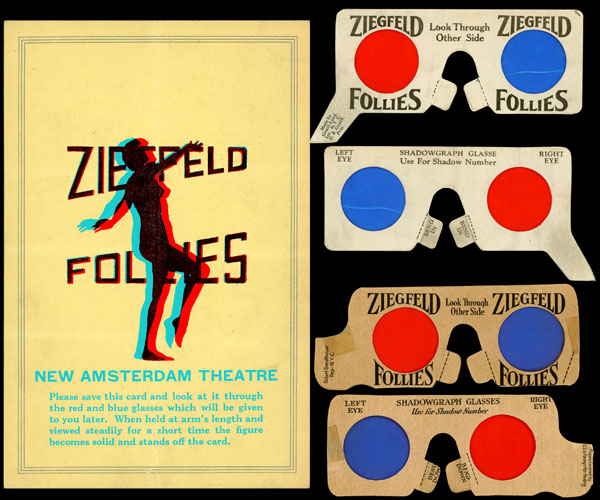

The 1923 Ziegfeld Follies opened 27OCT23, at the 1,700+ seat New Amsterdam Theatre, 214 West 42nd St, NYC.

The New Amsterdam Theatre in 1925.

To provide perspective of the caliber of this show, ticket prices were $22 in 1923 dollars. Best seats in the top movie houses were $1 or less. Yet the Follies often sold out as it was literally the best show in town. Yes, the nose bleed sections were MUCH cheaper. Today, that ticket would be about $256.

This

This

For about 15 minutes during the three hour show, the audience was blown away by a totally new idea in entertainment.

Ziegfeld was unsure of this gimmick, as evidenced by his not advertising the act until 23 days later, on 19NOV23, as “Shadowgraph, the scream of the decade. Most sensational novelty ever produced.”

It is unknown if the shadowgraph stayed with the Follies for its 233 performances (ending 10MAY24).

Anaglyph handbill and various versions of the glasses.

Hammond’s patent was granted on 15JAN24.

Because the patent had no legal effect until the issue date, the Duke of York’s Theatre in London opened Andre Charlot’s production of LONDON CALLING on 4SEP23, featuring a stereoscopic shadowgraph act. Apparently a few of the musical numbers were written by the up-and-coming Noel Coward, who also was in the revue. I have no further details at this time though the production continued for 316 performances well into 1924.

Duke of York's Theatre, London, has changed little since '23.

Hammond mentioned going abroad to try to collect royalties for uses of his patented idea, though apparently didn’t have much luck. It’s likely many major European cities hosted shadowgraph shows at the time. Hammond did say he sold rights to the shadowgraph to a Chinese promoter for $2,000 (nearly $23,000 today).

There was an announcement in The Washington Post 9MAR1930 of “The Shadowgraph (third dimensional illusory effect)” starting 16MAR at the National Theater, in George E. Wintz’s revue, VANITY FAIR OF 1930. There’s no information connecting Hammond.

It was in 1934 that Hammond hit the big time with his invention of the Hammond organ. I’ll leave THAT story to others.

The stereoscopic shadowgraph was amazing entertainment, and would still excite today. But it is a very limited medium, and practical only for short programs.